I was having a discussion with someone the other day regarding the use of plywood in the skin-on-frame kayaks and canoes that I'm building this person took exception to the fact that plywood could be a "traditional material" while my build method I consider to be "non-traditional". While the building method is non-traditional in that I don't use steam-bent ribs to provide hoop strength in the hull of the boat, I really do consider plywood to be a traditional building material.

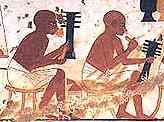

How so you say? Plywood has been around as a building material since the ancient Egyptians. Check this out:

The oldest piece of plywood was found in a third dynasty coffin, made of six layers of wood each 4 mm thick and held together by wooden pegs. [11] Like modern plywood the grain of its layers was arranged crosswise to give it added strength. [12] From 1750 BCE onwards this plywood technique became widespread. The thickness of the layers was reduced to less than three millimetres and they were stuck together with a glue made from bone, sinew and cartilage applied hot. [13]

(http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/timelines/topics/wood.htm)

So, why is plywood such a great material? Well, for one thing, it usually starts out flat and rectangular in common sizes. The use of unequal numbers of layers (or plies) of wood helps to keep the plywood from warping. It's made from layers of wood with the grain of the plies at 90° to one-another and bonded together. This makes it relatively dimensionally stable with changes in moisture content. It can be formed to make shapes. It doesn't split all the way through if you nail or screw it together without pre-drilling. The strength is consistent in both directions. It generally takes finish well. It doesn't tend to check through and through. It can have decorative veneers on the faces to be pretty. The adhesives used to bond the sheets together can be made from water resistant resins. The use of some modern marine plywoods have made some great boat designs affordable and achievable by those without extensive woodworking or boat building skills.

All of those things being said, not all plywood is created equally - there are softwood, hardwood, marine, aircraft and decorative plywoods to name just a few. Some plywoods have voids or patches in the middle or outer laminations. Some have no flaws allowed on the exterior, but voids or patches allowed on the interior. Whatever your application, be sure to select the best plywood for your application and remember the long history of this venerable material. Above all, don't forget to do your homework!