Enjoy!

Love Boats: The Delightfully Sinful History of Canoes

By Hunter Oatman-Stanford

Before the youth of America fooled around at drive-ins and necked on

Lover’s Lane, they coupled in canoes. Boatloads of them. In the early

1900s, canoes offered randy young guys and gals a means of escape to a

semi-private setting, away from the prying eyes of their pious Victorian

chaperones.

“To go canoeing on the weekend was pretty much what you did with your

best girl,” says canoe enthusiast and collector Roger Young. “There

weren’t a whole lot of motorcars around at that time. You could go bicycling, but to go out canoeing was the thing.”

These canoes weren’t your typical summer camp variety; they were

designed for afternoons (and evenings) of stylish leisure. Most boaters

accessorized them with pillows, lanterns, and picnicking supplies. Some

even customized their canoes with built-in phonographs—floating boom-boxes for the paddle set.

“One Minneapolis Tribune headline read ‘Girl Canoeists’ Tight Skirts Menace Society’”

Adolescents took to the waters with the urgency of salmon fighting

their way upstream, spawning a veritable canoe craze, particularly in

places like Boston along the Charles River and at Belle Isle, near

Detroit. While any canoe would do, companies such as Old Town, Kennebec,

and White marketed “courting canoes” specifically designed for

waterborne lovebirds. “These boats usually had long 4-foot decks and an

8-foot elliptical or oval cockpit,” says Young. “The woman would sit in

the bottom of the canoe on cushions with her parasol to shade her from

the sun, while her gentleman in his boater hat would paddle and probably

croon to her. Or she might read poetry to him.” Make no mistake; these

were wild times.

Canoeing

duos enjoy a concert on the Grand Canal at Belle Isle Park, in Detroit

circa 1907. In the lower left-hand corner, two boaters take advantage of

canoe luxuries like reclining seats and phonograph music.

Image

courtesy Shorpy.com.

In North America, the earliest canoes weren’t meant for leisure; they

were used by Native Americans as a means of efficient transportation

along busy trade routes. During the late 1700s, the birch-bark canoe was

adopted by European settlers to aid with the booming fur industry, and

by the mid-1800s, entrepreneurs in the Peterborough region of Canada

modified the standard canoe design to a more durable wood-plank

construction.

Canoeing as a sport can be traced to Scottish lawyer John MacGregor,

who designed a type of covered canoe using both a sail and paddles that

he called the “Rob Roy.” MacGregor’s love of travel motivated him to

commission this specialized boat from Searle & Son of London in

1865. The resulting canoe had cedar decks and an oak hull, and at 15

feet long was just short enough to fit into a train car.

To help publicize the freedoms of solo canoe travel, MacGregor chose

popular routes through central Europe, like the Danube River, where he

experimented with his new craft and discussed its merits with locals.

The following year, he published a book about his experiences, espousing

the many virtues of travel by canoe. But even MacGregor, who was also

the inventor of the pleasure boat, noted that his craft offered plenty

of space for horizontal bliss, “with at least as much room for turning

in your bed as sufficed for the great Duke of Wellington.”

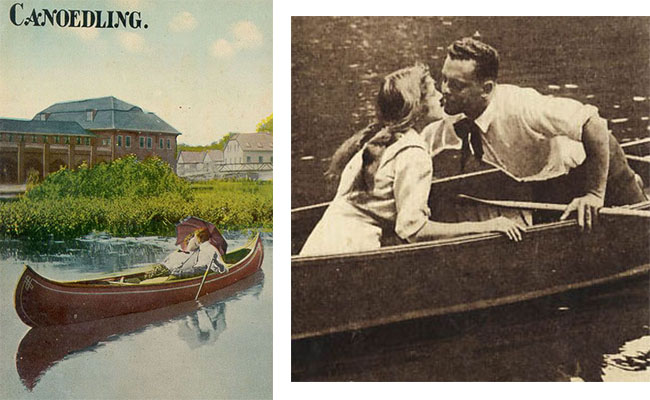

Two

postcards from the early 1900s capitalize on the popularity of

scandalous "canoedling," though the word most likely evolved from the

German term “knuddeln,” meaning “to cuddle.”

Left image courtesy Benson

Gray.

The concept of canoes as recreational vehicles was cemented. Regattas

and informal competitions spread throughout the 19th century, and a

centrally organized sporting group, the American Canoe Association, was

founded in 1880. Simultaneously, the industrialization and urbanization

of the factory world implemented new ideas about “weekends” and “free

time,” when people could enjoy personal interests and pursuits.

According to Benson Gray, the great-grandson of the Old Town Canoe

company’s founder, “urban populations were looking for something to do

on the weekends, and streetcar companies were more than happy to take

them out of the cities to local waterways where they could paddle around

in canoes.”

Increasing globalization also led to large international expositions,

like the Chicago World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, where various

styles of indigenous and modern canoes were presented to the public

alongside other technological marvels. Canoe clubs and rental facilities

soon popped up in parks across the country, from San Francisco to New

Orleans to New York City.

“In its heyday,” says Young, “thousands of young and even older folks

would turn out in these popular areas, so many that it was often said

you could cross the river without getting wet simply by stepping from

canoe to canoe. There were even policemen patrolling by canoe as

‘morality enforcement,’ making sure that everyone remained upright and

reputations remained intact.”

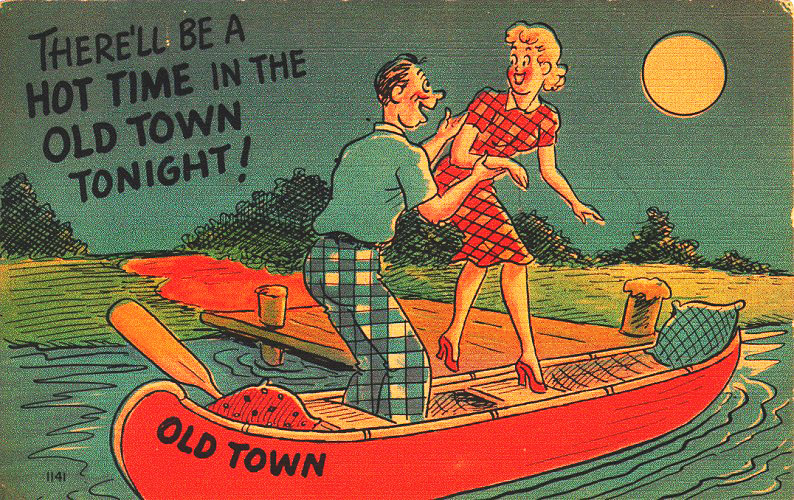

A comic postcard advertising Old Town Canoes makes an open joke of their preferred use.

Image courtesy Benson Gray.

In 1903, before the trend really took off, a “Boston Herald” article

scoffed at the effectiveness of puritanical boating ordinances: “It may

not be wicked to go canoeing on the Charles with young women on Sunday,

but we continue to be reminded that it is frequently perilous…The

canoeist arrested for kissing his sweetheart at Riverside was fined $20.

At that rate it is estimated that over a million dollars’ worth of

kisses are exchanged at that popular canoeing resort every fine Saturday

night and Sunday.”

A 1904 souvenir brochure for the Charles River area emphasized its

natural beauty and praised the healthful benefits of boat trips,

interspersing scenic photographs with lines of poetry. The pamphlet

began, “If you are fortunate enough to be canoeing at sunset…and to

spend an evening on the river during a concert or an illumination, to

see the canoes appearing one by one, tastily decorated with Japanese

lanterns, to hear the sweet tones of a passing guitar or the strains of

some glee club floating down stream, you can very easily imagine

yourself in Fairyland.” If the make-out potential of a canoe date wasn’t

clear enough, accompanying advertisements for no less than 10 different

chocolate companies drove the point home.

By 1912, in Minnesota, the undisputed lake capitol of the U.S., canoe

permits and rental spaces were off the charts. The Minneapolis Parks

Department’s 2,000 permit spaces were almost maxed out, and the city was

having a tough time enforcing its 12 a.m. lake curfew. A “Minneapolis

Tribune” story reported that, “misconduct in canoes has become so grave

and flagrant that it threatens to throw a shadow upon the lakes as

recreation resorts and to bring shame upon the city.” Regardless of the

curfew, a lot could happen in the dark hours between dusk and midnight,

inspiring park police to patrol the lakes for inappropriate behavior on

motorized boats equipped with spotlights.

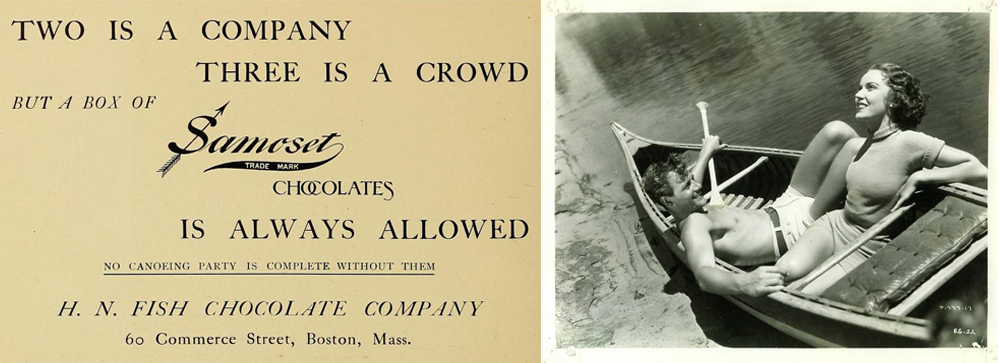

Left:

A canoe-centric advertisement for Samoset Chocolates worded to entice

romantic twosomes.

Right: Hollywood finally recognizes the potential of

sinful canoeing, over a decade too late, in a publicity still from the

1930s featuring Joel McCrea and Maureen O'Sullivan.

As further proof that canoeing had become a hotbed for teenage

delinquents, in 1913 the Minneapolis Parks Board refused to issue

permits for canoes with unpalatable names. Local newspapers published

some of the offensive phrases that slipped past the board the previous

summer, including “Thehelusa,” “Kumomin Kid,” “Kismekwik,” “Damfino,”

“Ilgetu,” “Aw-kom-in,” “G-I-Lov-U,” “Skwizmtyt,” “Ildaryoo,”

“Win-kat-us,” “O-U-Q-T,” “What the?,” “Joy-tub,” “Cupid’s Nest,” and “I

Would Like to Try It.” The commissioners unanimously agreed to outlaw

phrases lacking obvious moral and grammatical standards, though a few of

these clever pre-text-message abbreviations clearly had them scratching

their heads.

Meanwhile, the drama was heightened by a frenzied headline printed by

the “Tribune” in June of 1914: “Girl Canoeists’ Tight Skirts Menace

Society,” it wailed. In the article itself, F.C. Berry, a supposed park

expert on recreational features, warned of the dangers narrow skirts

posed to female boaters—in the event of a capsize, they’d be unable to

swim.

A

postcard from 1906 advertises the supposedly chaste pleasures of

night-time boating on the Charles River near Boston.

Image courtesy

Newton Conservators.

Whether or not any actual drownings were attributed to tight skirts,

safety wasn’t the top concern for most canoers; a boat’s ability to hold

two passengers, preferably side by side, was generally of higher

priority. Though the Minneapolis Parks Board attempted to institute an

ordinance requiring opposite sex couples (over age 10) to sit facing

each other, public outcry helped to quickly repeal the restriction.

By 1916, the canoe-courting trend was widespread enough to warrant

mention in a musical comedy called “Tres Rouge” by Jay Gorney, which

included a song called “Out in My Old Town Canoe.” But this floating,

petting paradise would not last. “When motorcars became more available

in the early ’20s, courting in canoes sort of fell off,” says Young.

“Guys were getting into their Model Ts or Model As and going off with

girls for a Sunday drive instead of canoeing.” And what went on in the

backseats of those cars? Well, that’s a whole different story.

(Thanks to Benson Gray, Roger Young, Dave Smith, Shorpy, Newton Conservators)

No comments:

Post a Comment