Friday, August 31, 2012

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Va-Va-Va-Voom!

This little piece of historical wonder from the Collector's Weekly website was posted at the WoodenBoat Forum today and was too good not to pass along. Both Benson Gray and Roger Young are active in the WCHA and provided some great information for this article.

Enjoy!

By Hunter Oatman-Stanford

(Thanks to Benson Gray, Roger Young, Dave Smith, Shorpy, Newton Conservators)

Enjoy!

Love Boats: The Delightfully Sinful History of Canoes

July 5th, 2012

Before the youth of America fooled around at drive-ins and necked on

Lover’s Lane, they coupled in canoes. Boatloads of them. In the early

1900s, canoes offered randy young guys and gals a means of escape to a

semi-private setting, away from the prying eyes of their pious Victorian

chaperones.

“To go canoeing on the weekend was pretty much what you did with your

best girl,” says canoe enthusiast and collector Roger Young. “There

weren’t a whole lot of motorcars around at that time. You could go bicycling, but to go out canoeing was the thing.”

These canoes weren’t your typical summer camp variety; they were

designed for afternoons (and evenings) of stylish leisure. Most boaters

accessorized them with pillows, lanterns, and picnicking supplies. Some

even customized their canoes with built-in phonographs—floating boom-boxes for the paddle set.

“One Minneapolis Tribune headline read ‘Girl Canoeists’ Tight Skirts Menace Society’”

Adolescents took to the waters with the urgency of salmon fighting

their way upstream, spawning a veritable canoe craze, particularly in

places like Boston along the Charles River and at Belle Isle, near

Detroit. While any canoe would do, companies such as Old Town, Kennebec,

and White marketed “courting canoes” specifically designed for

waterborne lovebirds. “These boats usually had long 4-foot decks and an

8-foot elliptical or oval cockpit,” says Young. “The woman would sit in

the bottom of the canoe on cushions with her parasol to shade her from

the sun, while her gentleman in his boater hat would paddle and probably

croon to her. Or she might read poetry to him.” Make no mistake; these

were wild times.

Canoeing

duos enjoy a concert on the Grand Canal at Belle Isle Park, in Detroit

circa 1907. In the lower left-hand corner, two boaters take advantage of

canoe luxuries like reclining seats and phonograph music.

Image

courtesy Shorpy.com.

In North America, the earliest canoes weren’t meant for leisure; they

were used by Native Americans as a means of efficient transportation

along busy trade routes. During the late 1700s, the birch-bark canoe was

adopted by European settlers to aid with the booming fur industry, and

by the mid-1800s, entrepreneurs in the Peterborough region of Canada

modified the standard canoe design to a more durable wood-plank

construction.

Canoeing as a sport can be traced to Scottish lawyer John MacGregor,

who designed a type of covered canoe using both a sail and paddles that

he called the “Rob Roy.” MacGregor’s love of travel motivated him to

commission this specialized boat from Searle & Son of London in

1865. The resulting canoe had cedar decks and an oak hull, and at 15

feet long was just short enough to fit into a train car.

To help publicize the freedoms of solo canoe travel, MacGregor chose

popular routes through central Europe, like the Danube River, where he

experimented with his new craft and discussed its merits with locals.

The following year, he published a book about his experiences, espousing

the many virtues of travel by canoe. But even MacGregor, who was also

the inventor of the pleasure boat, noted that his craft offered plenty

of space for horizontal bliss, “with at least as much room for turning

in your bed as sufficed for the great Duke of Wellington.”

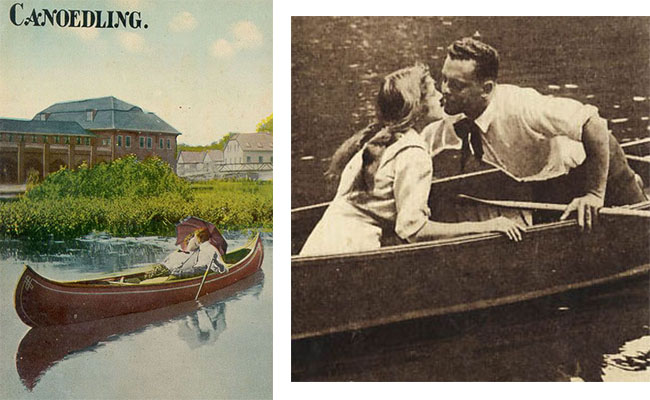

Two

postcards from the early 1900s capitalize on the popularity of

scandalous "canoedling," though the word most likely evolved from the

German term “knuddeln,” meaning “to cuddle.”

Left image courtesy Benson

Gray.

The concept of canoes as recreational vehicles was cemented. Regattas

and informal competitions spread throughout the 19th century, and a

centrally organized sporting group, the American Canoe Association, was

founded in 1880. Simultaneously, the industrialization and urbanization

of the factory world implemented new ideas about “weekends” and “free

time,” when people could enjoy personal interests and pursuits.

According to Benson Gray, the great-grandson of the Old Town Canoe

company’s founder, “urban populations were looking for something to do

on the weekends, and streetcar companies were more than happy to take

them out of the cities to local waterways where they could paddle around

in canoes.”

Increasing globalization also led to large international expositions,

like the Chicago World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, where various

styles of indigenous and modern canoes were presented to the public

alongside other technological marvels. Canoe clubs and rental facilities

soon popped up in parks across the country, from San Francisco to New

Orleans to New York City.

“In its heyday,” says Young, “thousands of young and even older folks

would turn out in these popular areas, so many that it was often said

you could cross the river without getting wet simply by stepping from

canoe to canoe. There were even policemen patrolling by canoe as

‘morality enforcement,’ making sure that everyone remained upright and

reputations remained intact.”

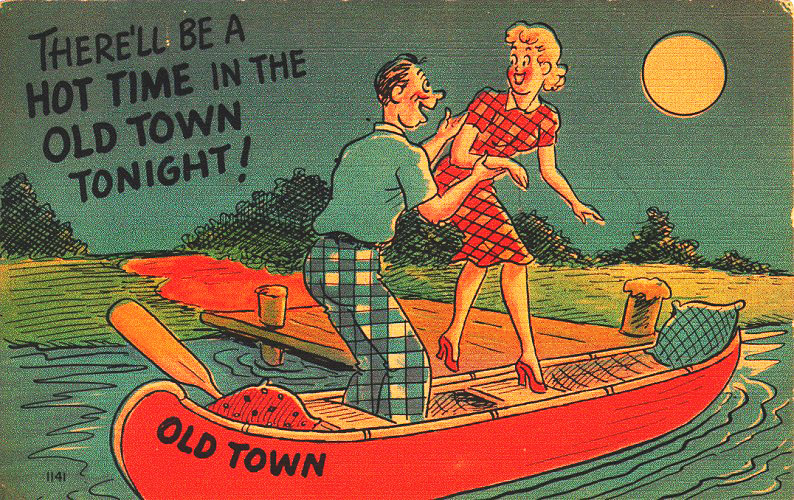

A comic postcard advertising Old Town Canoes makes an open joke of their preferred use.

Image courtesy Benson Gray.

In 1903, before the trend really took off, a “Boston Herald” article

scoffed at the effectiveness of puritanical boating ordinances: “It may

not be wicked to go canoeing on the Charles with young women on Sunday,

but we continue to be reminded that it is frequently perilous…The

canoeist arrested for kissing his sweetheart at Riverside was fined $20.

At that rate it is estimated that over a million dollars’ worth of

kisses are exchanged at that popular canoeing resort every fine Saturday

night and Sunday.”

A 1904 souvenir brochure for the Charles River area emphasized its

natural beauty and praised the healthful benefits of boat trips,

interspersing scenic photographs with lines of poetry. The pamphlet

began, “If you are fortunate enough to be canoeing at sunset…and to

spend an evening on the river during a concert or an illumination, to

see the canoes appearing one by one, tastily decorated with Japanese

lanterns, to hear the sweet tones of a passing guitar or the strains of

some glee club floating down stream, you can very easily imagine

yourself in Fairyland.” If the make-out potential of a canoe date wasn’t

clear enough, accompanying advertisements for no less than 10 different

chocolate companies drove the point home.

By 1912, in Minnesota, the undisputed lake capitol of the U.S., canoe

permits and rental spaces were off the charts. The Minneapolis Parks

Department’s 2,000 permit spaces were almost maxed out, and the city was

having a tough time enforcing its 12 a.m. lake curfew. A “Minneapolis

Tribune” story reported that, “misconduct in canoes has become so grave

and flagrant that it threatens to throw a shadow upon the lakes as

recreation resorts and to bring shame upon the city.” Regardless of the

curfew, a lot could happen in the dark hours between dusk and midnight,

inspiring park police to patrol the lakes for inappropriate behavior on

motorized boats equipped with spotlights.

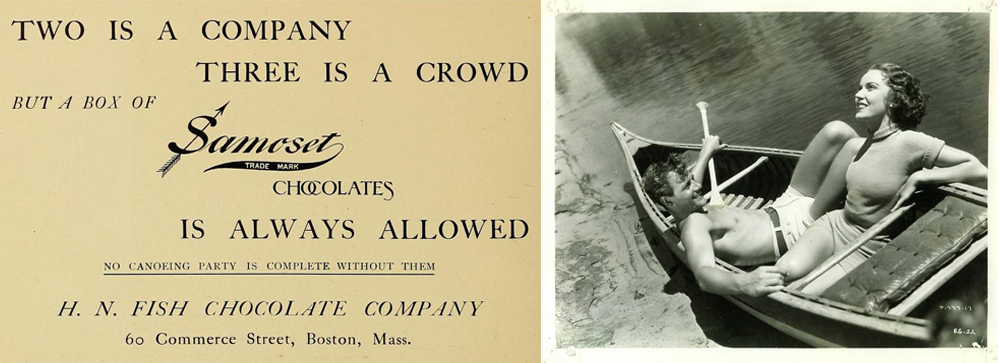

Left:

A canoe-centric advertisement for Samoset Chocolates worded to entice

romantic twosomes.

Right: Hollywood finally recognizes the potential of

sinful canoeing, over a decade too late, in a publicity still from the

1930s featuring Joel McCrea and Maureen O'Sullivan.

As further proof that canoeing had become a hotbed for teenage

delinquents, in 1913 the Minneapolis Parks Board refused to issue

permits for canoes with unpalatable names. Local newspapers published

some of the offensive phrases that slipped past the board the previous

summer, including “Thehelusa,” “Kumomin Kid,” “Kismekwik,” “Damfino,”

“Ilgetu,” “Aw-kom-in,” “G-I-Lov-U,” “Skwizmtyt,” “Ildaryoo,”

“Win-kat-us,” “O-U-Q-T,” “What the?,” “Joy-tub,” “Cupid’s Nest,” and “I

Would Like to Try It.” The commissioners unanimously agreed to outlaw

phrases lacking obvious moral and grammatical standards, though a few of

these clever pre-text-message abbreviations clearly had them scratching

their heads.

Meanwhile, the drama was heightened by a frenzied headline printed by

the “Tribune” in June of 1914: “Girl Canoeists’ Tight Skirts Menace

Society,” it wailed. In the article itself, F.C. Berry, a supposed park

expert on recreational features, warned of the dangers narrow skirts

posed to female boaters—in the event of a capsize, they’d be unable to

swim.

A

postcard from 1906 advertises the supposedly chaste pleasures of

night-time boating on the Charles River near Boston.

Image courtesy

Newton Conservators.

Whether or not any actual drownings were attributed to tight skirts,

safety wasn’t the top concern for most canoers; a boat’s ability to hold

two passengers, preferably side by side, was generally of higher

priority. Though the Minneapolis Parks Board attempted to institute an

ordinance requiring opposite sex couples (over age 10) to sit facing

each other, public outcry helped to quickly repeal the restriction.

By 1916, the canoe-courting trend was widespread enough to warrant

mention in a musical comedy called “Tres Rouge” by Jay Gorney, which

included a song called “Out in My Old Town Canoe.” But this floating,

petting paradise would not last. “When motorcars became more available

in the early ’20s, courting in canoes sort of fell off,” says Young.

“Guys were getting into their Model Ts or Model As and going off with

girls for a Sunday drive instead of canoeing.” And what went on in the

backseats of those cars? Well, that’s a whole different story.

(Thanks to Benson Gray, Roger Young, Dave Smith, Shorpy, Newton Conservators)

Labels:

Canoe,

Old Town,

passion,

Traditional,

WCHA,

WoodenBoat

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Tech Tip Tuesday

One of the things you learn pretty quickly when you start building boats - and I mean any kind of boat - is that you must become a skilled tradesman at many different things. The only thing that I have been unable to make on my own boats (other than weaving fiberglass or mixing epoxy and varnish...) is hardware. Bronze hardware, that is.

I have long desired to brush up my casting skills. When I was in high school, I was fortunate enough to go to a public high school that still had a "manual arts" program which included drafting, woodworking and metal working. As a freshman, you could take a class that was structured so that you got an introduction to all three. In the metal shop, you learned some sheet metal work, aluminum casting, lathe and milling skills along with some basic welding and brazing. Pretty cool, really. I must say, when the high school was renovated, they removed the metal and wood shops - probably due to cost and liability. I think that was a huge mistake for kids who would go on to study engineering disciplines in college. Anyway...

The WoodenBoat School in Brooklin, Maine offers some great classes - if you have any interest in boats, boating or related arts and crafts, you owe it to yourself to go there. It's summer camp for adults. One of the classes they offer is a bronze casting class that is taught by Sam Johnson. Sam got his start in casting when he wanted to get a copy of a port light that he had on his boat. He approached a foundry regarding a copy of the port light and was appalled at the price they wanted. He taught himself how to cast bronze and replicated the parts himself - learning how cheap the original quote truly was in the process.

I'd seen some of the results of Sam's classes when I was at WoodenBoat before, seen his demonstration at Mystic Seaport during the WoodenBoat Show and had heard good things from previous students of his. Back in December, when the school's catalog came out, I made up my mind that this would be the year for me to work on those skills.

The class was a wonderful hands-on class where we were learning the skills to sand-cast bronze hardware. For the uninitiated, sand casting is a process by which you use a master pattern to create a part-shaped void in special oil sand with risers and gates to allow you to pour molten metal into the void. When the metal cools, you have your part.

On our first day, we started out learning about how the process works - from a very basic perspective. We started with instruction regarding safety in the foundry. It is imperative to wear leather shoes, long cotton pants, safety glasses, welding gloves and preferably, long-sleeved cotton shirts. The temperatures required to pour bronze are around 2,200° Fahrenheit (just over 1,200° centigrade for those working in the metric system) - really, really hot. The other important safety tip is to make sure that any metal or crucibles are both dry and hot before going into the furnaces - moisture at that temperature will flash to steam and can cause a steam explosion, splashing molten metal out of the crucible. We then delved into the construction of home-made propane-fired furnaces, tongs, crucible holders, and other items that were used in the process. With the exception of the petro-bond sand (Graded sand that is coated with clay and then oiled to make it stick together), crucibles (Ceramic flask in which the metal is melted) and a few special items, pretty much everything was hand made or readily available in local stores.

Sam then showed us how to make the mold for a simple part. The part looks basically like a bronze tuning fork and is used in the molding process with an awl to gently tap the patterns, gates and risers out of the sand.

The first thing you do is to place a small piece of plywood, just larger than the base of the flask (The two-part wooden frame used to hold the sand.) on your bench. You then separate the cope (top of the flask) and the drag (bottom of the flask) Putting the cope aside and then flipping the drag upside down on the board (the bottom must be facing you for the process to work), you then put the pattern (Wood, plaster or plastic copy of the part to be molded), or part to be molded, on the surface of the board along with a piece of wood to form the runner (A channel for the molten metal to flow inside the mold). Placement can't be too close to the edge or too close together to avoid having the bronze push out through a sidewall or burn the wooden flasks that we were using, or having the runner bleed into the part.

You then apply a parting compound - a powdery substance used as a mold release to let the patterns and runners be easily pulled from the mold. It also keeps the sand from sticking to itself. We used both Calcium Carbonate and Corn Starch depending on the conditions. Sand was then sieved in using a riddle (a box with a fine screen on the bottom) to get good detail of the parts. More sand was then shoveled in and rammed into place with a piece of steel bar. The sand should be firmly packed, but not to hard to allow gasses to escape. This helps to yield a good surface finish. Once the drag was slightly over-filled, a stick was used to strike off the excess sand yielding a flat surface on the bottom of the drag.

The drag was then flipped over using the plywood to support the sand. The cope was installed to complete the flask. A gate block (Basically a small runner to connect the part to the runner.) was then put on top of the runner and touching the top surface of the part to connect them. More parting compound was applied and a riser (A tapered piece with a square cross-section used to feed molten metal from the outside world to the runner. The riser has this shape to avoid swirling of the molten metal that would erode the sand, contaminating the part.) was held against the runner and more sand was riddled onto the parts and more sand shoveled and packed into place. The sand was basically packed in until it reached the top of the cope. A small area was scooped out adjacent to the riser with a melon-baller to provide a "pouring cup" The "tuning fork" was then used to tap the riser loose and it was gently pulled straight out of the sand. Loose sand was blown away and sharp, fine edges of sand were removed. The cope was gently removed and set aside exposing the gate, runner and part. An awl or gimlet was inserted into each part and tapped gently to loosen them in the sand and then they were removed. Care was taken to blow out loose particles of sand and to keep sharp edges around the part. This helps to yield a high-quality part without "flash" at the edge of the part.

The cope was then re-installed on the drag and they were clamped together. This is important as the metal is so dense, when you pour in the molten bronze, the cope can float off the drag spilling hot metal everywhere. (Don't ask me how I know this...) Supporting the assembled sand mold on a piece of plywood, Sam brought it over to the casting area. Removing the top from the furnace, he used a scoop to remove slag (Metal oxides, sulfides and contaminants.) from the crucible. Picking up the tongs, he pulled the crucible from the furnace and in one smooth motion, poured the bronze into the pouring cup and filled the mold. After a few minutes, he broke of the pouring cup (to return to the crucible) and after a few more minutes broke open the mold to reveal the new part, still attached to gate, runner and riser. Some quick sawing and sanding yielded the finished product.

This simplifies the description of the process somewhat as there are some "tricks to the trade". I won't reveal them all - you should go learn for yourself if you're interested! Basically, the rest of the week built on that process - how to make patterns and how to get complex items out of the sand - parts with undercuts, odd shapes and the like - the real challenge is how to get them out of the sand. Also, the metal shrinks as it cools, so you have to deal with this when recreating parts that require close dimensions.

Here's some pictures of a more complex part - a jib ring - being made. (No, the person shown isn't me or Sam, he's a fellow student.)

As I've noted, we got lots of practice casting and made quite a few parts. Pulleys, a mermaid fid, a sounder and many others. Some folks brought parts or patterns they wanted to reproduce. One fellow brought a pattern for a bracket to hold a signaling canon that he'd made to his boat's rail. He hadn't known enough about pattern making and the gate for the part was problematic. Sam suggested a horn riser and described what it was and how it worked. The student went and made it proceeded to successfully pour the part. Sam later told him that it was something that he, himself hadn't tried, but had read about!

One of the major reasons that I went was to try to make a set of pad-eyes to mount on the canoe decks. Ultimately I want to create something that's a little bit fancier than this, but it was a good first try. Here's the pattern:

In the top right is a core-box. It's used to create a sand shape to fill the cavity left when the master pattern is removed from the sand. The leaf-looking thing is the master pattern with a half-round shape that will be filled by the core. The two smaller pieces are the bosses which attach to the back of the master pattern in the top half of the mold. The bosses would later be tapped to allow for machine screws that would hold the part from underneath the deck. When the part was removed from the mold, it looked like this:

After removing the runner and gates, I had this:

We spent a fair amount of time learning how to finish our parts as well - sanding, grinding, filing and pollishing the parts. We also learned a bit about applying various patinas to the bronze.

I'll end the post like the end of every day - with the pouring of ingots to empty the crucibles:

I have long desired to brush up my casting skills. When I was in high school, I was fortunate enough to go to a public high school that still had a "manual arts" program which included drafting, woodworking and metal working. As a freshman, you could take a class that was structured so that you got an introduction to all three. In the metal shop, you learned some sheet metal work, aluminum casting, lathe and milling skills along with some basic welding and brazing. Pretty cool, really. I must say, when the high school was renovated, they removed the metal and wood shops - probably due to cost and liability. I think that was a huge mistake for kids who would go on to study engineering disciplines in college. Anyway...

The WoodenBoat School in Brooklin, Maine offers some great classes - if you have any interest in boats, boating or related arts and crafts, you owe it to yourself to go there. It's summer camp for adults. One of the classes they offer is a bronze casting class that is taught by Sam Johnson. Sam got his start in casting when he wanted to get a copy of a port light that he had on his boat. He approached a foundry regarding a copy of the port light and was appalled at the price they wanted. He taught himself how to cast bronze and replicated the parts himself - learning how cheap the original quote truly was in the process.

I'd seen some of the results of Sam's classes when I was at WoodenBoat before, seen his demonstration at Mystic Seaport during the WoodenBoat Show and had heard good things from previous students of his. Back in December, when the school's catalog came out, I made up my mind that this would be the year for me to work on those skills.

The class was a wonderful hands-on class where we were learning the skills to sand-cast bronze hardware. For the uninitiated, sand casting is a process by which you use a master pattern to create a part-shaped void in special oil sand with risers and gates to allow you to pour molten metal into the void. When the metal cools, you have your part.

On our first day, we started out learning about how the process works - from a very basic perspective. We started with instruction regarding safety in the foundry. It is imperative to wear leather shoes, long cotton pants, safety glasses, welding gloves and preferably, long-sleeved cotton shirts. The temperatures required to pour bronze are around 2,200° Fahrenheit (just over 1,200° centigrade for those working in the metric system) - really, really hot. The other important safety tip is to make sure that any metal or crucibles are both dry and hot before going into the furnaces - moisture at that temperature will flash to steam and can cause a steam explosion, splashing molten metal out of the crucible. We then delved into the construction of home-made propane-fired furnaces, tongs, crucible holders, and other items that were used in the process. With the exception of the petro-bond sand (Graded sand that is coated with clay and then oiled to make it stick together), crucibles (Ceramic flask in which the metal is melted) and a few special items, pretty much everything was hand made or readily available in local stores.

Sam then showed us how to make the mold for a simple part. The part looks basically like a bronze tuning fork and is used in the molding process with an awl to gently tap the patterns, gates and risers out of the sand.

The first thing you do is to place a small piece of plywood, just larger than the base of the flask (The two-part wooden frame used to hold the sand.) on your bench. You then separate the cope (top of the flask) and the drag (bottom of the flask) Putting the cope aside and then flipping the drag upside down on the board (the bottom must be facing you for the process to work), you then put the pattern (Wood, plaster or plastic copy of the part to be molded), or part to be molded, on the surface of the board along with a piece of wood to form the runner (A channel for the molten metal to flow inside the mold). Placement can't be too close to the edge or too close together to avoid having the bronze push out through a sidewall or burn the wooden flasks that we were using, or having the runner bleed into the part.

You then apply a parting compound - a powdery substance used as a mold release to let the patterns and runners be easily pulled from the mold. It also keeps the sand from sticking to itself. We used both Calcium Carbonate and Corn Starch depending on the conditions. Sand was then sieved in using a riddle (a box with a fine screen on the bottom) to get good detail of the parts. More sand was then shoveled in and rammed into place with a piece of steel bar. The sand should be firmly packed, but not to hard to allow gasses to escape. This helps to yield a good surface finish. Once the drag was slightly over-filled, a stick was used to strike off the excess sand yielding a flat surface on the bottom of the drag.

The drag was then flipped over using the plywood to support the sand. The cope was installed to complete the flask. A gate block (Basically a small runner to connect the part to the runner.) was then put on top of the runner and touching the top surface of the part to connect them. More parting compound was applied and a riser (A tapered piece with a square cross-section used to feed molten metal from the outside world to the runner. The riser has this shape to avoid swirling of the molten metal that would erode the sand, contaminating the part.) was held against the runner and more sand was riddled onto the parts and more sand shoveled and packed into place. The sand was basically packed in until it reached the top of the cope. A small area was scooped out adjacent to the riser with a melon-baller to provide a "pouring cup" The "tuning fork" was then used to tap the riser loose and it was gently pulled straight out of the sand. Loose sand was blown away and sharp, fine edges of sand were removed. The cope was gently removed and set aside exposing the gate, runner and part. An awl or gimlet was inserted into each part and tapped gently to loosen them in the sand and then they were removed. Care was taken to blow out loose particles of sand and to keep sharp edges around the part. This helps to yield a high-quality part without "flash" at the edge of the part.

The cope was then re-installed on the drag and they were clamped together. This is important as the metal is so dense, when you pour in the molten bronze, the cope can float off the drag spilling hot metal everywhere. (Don't ask me how I know this...) Supporting the assembled sand mold on a piece of plywood, Sam brought it over to the casting area. Removing the top from the furnace, he used a scoop to remove slag (Metal oxides, sulfides and contaminants.) from the crucible. Picking up the tongs, he pulled the crucible from the furnace and in one smooth motion, poured the bronze into the pouring cup and filled the mold. After a few minutes, he broke of the pouring cup (to return to the crucible) and after a few more minutes broke open the mold to reveal the new part, still attached to gate, runner and riser. Some quick sawing and sanding yielded the finished product.

This simplifies the description of the process somewhat as there are some "tricks to the trade". I won't reveal them all - you should go learn for yourself if you're interested! Basically, the rest of the week built on that process - how to make patterns and how to get complex items out of the sand - parts with undercuts, odd shapes and the like - the real challenge is how to get them out of the sand. Also, the metal shrinks as it cools, so you have to deal with this when recreating parts that require close dimensions.

Here's some pictures of a more complex part - a jib ring - being made. (No, the person shown isn't me or Sam, he's a fellow student.)

Original Forged Iron Jib Ring

Drag with Part and Runner

Packed Cope with Riser and Pouring Cup

Prepared Mold Shown Open

Furnace and Pouring Area

Removing Slag

Hot Crucible!

Pouring Bronze

Cracking the Mold Open

Part with Gate, Runner and Riser

As I've noted, we got lots of practice casting and made quite a few parts. Pulleys, a mermaid fid, a sounder and many others. Some folks brought parts or patterns they wanted to reproduce. One fellow brought a pattern for a bracket to hold a signaling canon that he'd made to his boat's rail. He hadn't known enough about pattern making and the gate for the part was problematic. Sam suggested a horn riser and described what it was and how it worked. The student went and made it proceeded to successfully pour the part. Sam later told him that it was something that he, himself hadn't tried, but had read about!

One of the major reasons that I went was to try to make a set of pad-eyes to mount on the canoe decks. Ultimately I want to create something that's a little bit fancier than this, but it was a good first try. Here's the pattern:

In the top right is a core-box. It's used to create a sand shape to fill the cavity left when the master pattern is removed from the sand. The leaf-looking thing is the master pattern with a half-round shape that will be filled by the core. The two smaller pieces are the bosses which attach to the back of the master pattern in the top half of the mold. The bosses would later be tapped to allow for machine screws that would hold the part from underneath the deck. When the part was removed from the mold, it looked like this:

After removing the runner and gates, I had this:

After more clean up and a bit of polishing, we had these - not looking bad, eh?

We spent a fair amount of time learning how to finish our parts as well - sanding, grinding, filing and pollishing the parts. We also learned a bit about applying various patinas to the bronze.

I'll end the post like the end of every day - with the pouring of ingots to empty the crucibles:

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Spreading the Gospel

Had an interesting evening tonight. I went to give a talk about wooden canoes, kayaks and paddles at a craft school - basically a summer camp for adults - with the woman who built a skin-on-frame kayak with me. The school is interesting in that they are focused on the creative arts and crafts including (but not limited to!) glass work and blowing, fiber arts of various sorts, jewelry making, metal sculpture, woodworking, painting, and ceramics.

I was curious how we would be received as boat-builders. To draw attention to the talk that we were going to give near the dining hall, we put the two skin-on-frame kayaks, a cedar-strip canoe and an assortment of different paddles on the lawn where people could look at them before dinner. They garnered a pretty good bit of attention, which was nice to see. Some of the folks had no idea that people were still out there building their own boats and that it was possible for them to build something like we had on display.

So, if you're building a boat, don't hide your light under a bushel - share it with others!

I was curious how we would be received as boat-builders. To draw attention to the talk that we were going to give near the dining hall, we put the two skin-on-frame kayaks, a cedar-strip canoe and an assortment of different paddles on the lawn where people could look at them before dinner. They garnered a pretty good bit of attention, which was nice to see. Some of the folks had no idea that people were still out there building their own boats and that it was possible for them to build something like we had on display.

So, if you're building a boat, don't hide your light under a bushel - share it with others!

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)